A new little book, Wee Betsy, about that friendly and cleverest of Scottish travellers, Betsy Whyte, has just been published by her great-grandson David Pullar. It is written for young schoolchildren. I’m keenly waiting for my copy to arrive.

The appearance of Wee Bessie prompts me to write a blog sharing more of Betsy’s unpublished material which I recorded from her over the years. Her recordings are all archived at the Edinburgh University School of Celtic and Scottish Studies and on line at the Tobar an Dualchais website.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Betsy’s two classic autobiographies The Yellow on the Broom and Red Rowans and Wild Honey (Birlinn Books) date from around 40 years ago but still sell well and are now also available as digital books.

The most recent edition of Red Rowans now contains some new material, which Betsy had written shortly before her death in 1988. I quote a little of it here because I’ve been occupied recently, responding to the complaints of many residents in Sutton Coldfield (where I now live). My fellow Suttonians just don’t want travellers pitching up for a night or two anywhere in their ‘Royal’ town.

BETSY WROTE:-

“The end of the war was also the beginning of the end for the Scottish travelling people. With bewildering speed camping sites disappeared almost completely. Soon too, the farmers had machines which took over many jobs that the travelling folk had done. Even if a farmer did need workers, he was not allowed to have campers without providing flush toilets and running water, etc. Some farmers who grew a lot of berries did have those things put in, but for the majority it was not worth their while.

Then with full-time schooling becoming compulsory for the children of all house-holders, a time of flustration, vexation, and much misery began for most travellers. As there was no place to go they just had to live in a house, for the best part of the year at least.

Councils did provide houses, but very often the attitude of neighbours was very difficult to bear.

Sometimes non-travellers would get up a petition and take it to the council if they heard that a `tinker’ was to get a house in their street. If the petition was ignored unbearable misery was endured by the poor travelling family concerned. Their weans got the blame for every manner of wrong thing that happened in the neighbourhood. From pulling flowers in gardens, swinging on clothes-ropes, breaking windows with stones, to actual crimes like theft. Parents constantly drilled the bairns, took them to school, met them after school, kept them in, or if the father had an old car or van he would take them away with him to some park or country road.

Quite a few travellers found private sites to live on, if they had a caravan. There they could still have friends popping out and in, and keep some of their customs and habits alive.

Even in those sites however many things had to be given up, such as the pleasure of gathering around an open fire to have a sing-around and to play favourite musical instruments – the bagpipes, accordions and fiddles.

It was not always an easy matter to entertain a few friends inside caravans either, as the bairns couldn’t get to bed until the visitors left. Still, travellers thought, and many still do, that it was better than living in a house.

Many couldn’t find anywhere at all to live. With mechanisation taking over on the farms, they were not needed any more. So they wandered around, being moved on by the police, stealing a night here and there in lay-bys or some secluded spot.

It was impossible to school their families in such circumstances and at the approach of a strange non-traveller man, the women would quake lest he was from the education authorities and would take away their bairns. By this time however most of the powers-that-be had come to realise the folly of taking clean, healthy, much cherished children away from their parents. Instead they found houses for those wanderers and persuaded them to live in them and school the wee ones. Reluctantly most of them complied, and the children discovered that they were being treated like all the other bairns in most schools. Somehow the war had changed people….”.

———————-

With the appearance if her two autobiographies this shy Traveller lady became quite a celebrity and was often invited to festivals to speak, sing and share tales from her large repertory of traveller songs and stories. I asked her once what this meant for her and her kin:-

Peter: Has Brycie [her husband] got used to all the attention that you’re getting, yet?

Betsy: He just disnae understand it, cos he cannae see nothin’ in me, you see, other than jist his wife – that’s aa – a woman. And he cannae understand it, he thinks, he says, ‘They’re aa moich [mad], every one o’ them, they must be!’ Even the family’s a bit like that. They say, ‘God bless us woman, I dinnae ken how ye can be bothered,’ ye ken?

Peter: With the hantle? [non-travellers] Well, why are you bothered?

Betsy: Because I think I just like the attention, that’s the whole thing, I’ve never hed much attention in aa my life, never – me bein’ the third bairn that lived, like. There wis always – and then I wis always auld-fashioned – what they cry ‘auld-fashioned’ – grown up, understandin’ of what ma mother hes hed tae dae, like that. And I never looked for attention for myself – it wis always the wee-er one, or something else, you see – that kind of way.

Peter: And now you enjoy it?

Betsy: Aye, I do, yes, it’s no use o’ denying it – I liket it.

Peter: And was that all though? You didn’t write, what is it, 160 pages of a book just to get attention.

Betsy: Well, I always knew that given the chance I had things that I could have done, Peter, lots of different things, that I could have made a good enough living in the world for masel. No’ just writin, other things as well.

Peter: Like what?

Betsy: Well – especially nowadays, helping people who are goina tae be divorced or feeling really depressed an aa that.

Peter: A counsellor, you mean?

Betsy: Something like that… Or if I’d got mair education, as somebody in an office or something like that, you ken, I could have done these things. But I gave them aa up just tae – never tried anything and then – to have something like this happen to you at my age – it makes you really feel, it makes your life. You just say, ‘Well I hav’nae lived in vain after aa,’ you ken? There’s been something in it.

Peter: But you haven’t lived in vain in any case, have you? You’ve raised a family and you’re sustaining a husband, and so on.

Betsy: Well – yes – but it disnae seem – it’s just a sort o’ monotonous thing isn’t it, the usual run o’ things. But its something different, you see, to make your life –

Peter: Do your children regard you as being very different?

Betsy: Yes, they do, but I think they appreciate it.

Peter: Now how have they reacted to all the attention, now?

Betsy: Well, mixed feelings I think. They just sort of – ‘What is she tryin tae dae? She’s gaunnae make a fool o’ hersel,’ or something like this. And I’ve seen young Brycie sayin’ tae me ‘Oh Ma! How could ye dae that?’ If say, I’m goin up and singin. He says, ‘How could ye?’ I says, ‘Well, I just did it.’ I said, ‘I just made up my mind I could go and do anything like that.’

….Because I do that through the berry fields, even baddie [bawdy] songs and things like that – through the drills and through the tattie fields and right aboot. An at first they used tae feel a bit ashamed, ye ken, the laddies. But now, they’d think something was wrong if I didnae dae it. Because it seemed to get the whole lot of workers in a good mood.

Peter: Yes. What sort of songs there were your favourites, in the tattie fields?

Betsy: Well, mostly baddie songs!

Peter: Can I hear one?

Betsy: Well, I don’t know if I can mind any just now. Well now, something like – na, na! I think they are too baddie for y-

Peter: Go on! You’d be surprised at what we’ve got on tape in the archives.

Betsy: Aye. I suppose so. Well, just er, maybe me and Katie in the field and her a bittie over, and this is just a sort o’ wee example – it’s no’ that baddie. And er, I would start singing:-

‘There was an old woman sat shitin’ – and she would sing back, ‘At the back o’ a farm dyke,’ And then I would say, ‘The farmer came along and said, “You can’t shite there,”‘ And she’d answer, ‘She says, “A’ll shite there if I like.” ‘ And I’d say – ‘No, you’ll no’ shite there.’ She’d answer ‘Aye I will shite there,’

And we’d go on like this. And then, the other ones would listen and say ‘Who’s that? – Oh, that’s Bessie and Katie again.’ And then the whole field within a few minutes wis cheery, you ken…..

Peter: What is it about a blue song, a ‘baddie,’ that makes people so cheery?

Betsy: Ah, I don’ know. I don’ know. But it disnae have tae be a baddie, ye ken. No.

Peter: It has to be funny then?

Betsy: No, it disnae have to be funny either, it’s just the singin’ can change a whole room of people, or even a whole field full of people, when they’re aa workin’ close together. It can change them. I’ve noticed that often, that singing can change – even in the hoose. When ye start singing tae yirsel, and the right thoughts will come in your mind, about the thing, while you’re singing, if the song has a bearing on the situation, on the mood, you ken, – and you begin to…

Peter: That’s doing it to yourself. But in the potato field there’s a whole crowd..

Betsy. There’s a whole crowd there and ye dae something silly, like singing sangs aboot this and that…. So that if you were probably speaking tae any o’ the folks that I work wi’ in Montrose, they’d say, ‘Oh, she’s an awfie wifie that,’ ye ken, ‘She’s an awfie wifie.’ And – then other ones that jist sees you goin aboot the street that hesnae worked wi’ you, they could see you in a different light, completely.

But I think on the whole folk prefer that tae being stuffy, you ken, no matter what class o’ folk. But there are some – and it’s so stupid, just like where I stay just now in that building [a small council flat] – and then down where Katie stays, they’re mostly that type o’ folk and they’re really great neighbours tae have, they’d dae anything for you at any time o’ the night. But where I live they consider themselves a wee bit different you see. So that I couldnae gae oot on the green there and start singing something like that! But I could do that down where Katie is and I’d have them all oot ‘Come on, Bessie!,’ you ken,’ You bugger, come on!’ And it makes their day as well as mine, because I’m laughing at what I’m daein, I’m laughing for an entirely different reason from what they’re laughing at, so – you ken.

Peter: How do you mean?

Betsy: Well, I’m laughing at masel’ daein’ such things.

Peter: But they’ll be amused by it.

Betsy: This is what I’ll be laughin’ at. But – I’ve done it often tae help them in the fields. You feel so sorry for them because most o’ them mebbe have drunk men that comes and gives them a black ee or goes awa’ and drinks aa the money and disnae give them any. And they go oot and trauchle tae work and bring up their bairns and still adore their men, better than them that hes men that does everything for them, you ken. And their bairns – try their best for their bairns.

And if you were tae say, ‘Have you got – I forgot me fags.’ They’d be throwing them at you from all directions and leaving themselves withoot. This is the thing that I liked aboot these women that worked in the fields and that, you ken.

Peter: Yes. So really you’re a bit of an entertainer for them.

Betsy: In a way, and, if they – all their problems – they came tae me with them. ‘Bessie, [d’you] ken whit she said aboot me? -‘ and the other one’s coming too, greetin’ awa, you ken. And in a minute you had to be sort o’ diplomatic and keep them from fa’in oot and that. And – ‘Bessie, come and look at this bit. I’ve got a longer bit than she’s got,’ – at the tatties, you ken. And, ‘She’s pickin’ aff my drill,’ or ‘Somebody’s awa’ wi’ my basket,’ – and so on. You hed aa this tae – and it was up to me, they came wi’ this sort o’ thing – and the bairns as well.

Peter: You can help that person out. Did you ever have to tell somebody else where they got off? To try and restore..?

Betsy: No, I never do that among themselves. But if it was somebody else like the farmer or the gaffer, that was daein’ them an injustice, I’d tell him off. But if it wis among themselves, I’d try and get them tae be friends again. But often you got farmers that took advantage o’ they kind o’ folk.

————

But they were singing aa the time anyway. My mother sang an awful lot. She was always singing. She had songs for different moods, you kent her moods by the songs she was singing, even those songs when she was angry. This was it.

Peter: What songs would she sing if she was angry?

Betsy: It depended on what made her angry, you see, because she used to make up a lot o’ bits and put them in, that we kent whit she was meaning, but naebody else. But it was always like stampin-kind o’ ones when she was angry – marches, a tune o’ a march.

Peter: Can you mind any?

Betsy: Well no’ really, I could if I was takin’ time tae think about it but no’ just aff….

Peter: There were angry songs?

Betsy: She would take this -song – even an ordinary song that they were always singing and she’d put her ain bits in tae let them ken, instead of speaking tae them. Especially wi’ my father, the women and men always did that to each other.

Peter: They sang what they thought about?

Betsy: Aye! Sang words tae each other instead o’ speakin’, anything.

——————–

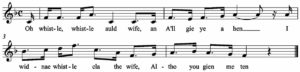

A wee bit of musical craik:

Oh whistle whistle, auld wife, and A’ll gie ye a hen, I widnae whistle, cla [replied?] the wife, altho you gien me ten.

Oh whistle whistle, auld wife, and A’ll gie you a cock, I wouldna whistle, cla the wife, gin you gied me a flock.

Oh whistle, whistle, auld wife, and A’ll gie ye a goon, I widnae whistle, cla the wife, for the best yin in the toon.

Oh whistle, whistle, auld wife, and A’ll gie ye a coo, I widnae whistle, cla the wife, although you gien me two.

Oh whistle whistle auld wife and A’ll gie ye a man, Oh wheeple, whapple, wheeple whap, A’ll try the best I can!

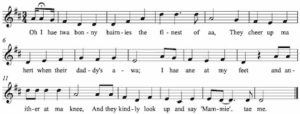

TWO LULLABIES

A baa buntin in, Daddie’s gone a huntin

Tae see would he get a lamb skin

Tae row (roll) his ain wee buntin in.

‘Mammie’ tae me. ‘Mammie’ tae me, They kindly look up and say ‘Mammie’ tae me.

Noo here’s the guidman comin hame fae the ploo, ‘It’s foo are ye wifie, and foo are ye noo, Oh, foo are ye wifie, and foo are ye noo, An foo’s the wee bairnies since I gaed awa?’

“That’s aa that I can remember o’ that one tae. My mother used to sing that one tae.”

ONE MORE:- Do you mind o’ that silly old man.

Betsy’s husband Bryce begins this one but gives up and Betsy continues.

Do ye mind on the silly old man Mama, …..

…..and he came yestreen,

Oh Ma, Mama, oh Ma she cried,

Do ye mind on yon silly old man.

Had I no care enough, Mama, Had I no care enough?

Had I no care enough, Mama?

Carried aff o’er that auld man

For he shoost me East and he shoost me West

And shoost me all aroond.

I wed him, I cled him and weel did I guide him

Till seven long years had passed

He shoost me North and he shoost me South

An he shoost me all aroond.

But oh how I niggled him, niggled, him, niggled him,

How I niggled that silly auld man

Come cradle me on your knee, Mama

Come cradle me on your knee.

Oh Ma, Mama, Mama she cried,

Come cradle me on your knee

everal of these lines are found in a poem called ‘The Child’s Dream‘ (or ‘The Infant’s Dream‘) by James Hyslop (23rd Jul. 1798 – 4th Dec. 1827) of Kirkconnel, Dumfriesshire. The poem was circulated amongst his friends, but also found its way into broadside ballads and other print sources.

————————-

AND A SHORT STORY:

Fish on Friday. [Told here to students during a ceilidh at Edinburgh University]

“Well, how many of you have heard it before? You have? Well it’s probably the same one.

Anyway, this young couple were very much in love. And the.. the lassie was a Catholic and the laddie was a Protestant. And long ago they were terribly zealous o’ their different religions, you see. So they had to meet on the sly and hide themselves every time they seen anybody that kent them.

And this went on for quite some time. But in the end, John says, ‘Look,’ he says, ‘I cannae go on like this Kathy , no way can I go on like this.’ He said, ‘It’s stupid.’ He said, ‘We’ll be runnin’ and hidin’ all the days of our life,’ he says, ‘I’m going to your father,’

She says, ‘Well you can please yirsel,’ she says, ‘if ye go to my father, but I ken what his answer will be.’

Anyhow, Sean went wi’ Kathy tae her house and asked tae see her father. And he said, ‘Look, we’re in love. Kathy and me are in love and we’ve been seeing each other for months and we want to get married.’

‘Aha!’ he says, ‘You’ll get married ower my dead body! No way,’ he says, ‘are you going to get my lassie. And you a Protestant? No, no, no. You’re no’ gettin’ Kathy’

And he says,’ Kathy, you gae into that bedroom and dinnae come oot o’ it,’ he says, ‘except tae your work,’ he says, ‘You’ll come straight hame – any other time you’re oot there’ll be somebody wi’ you. ‘ And he says, ‘You get aff o’ my door before I kick ye awa.’

So Sean went away, and his tail between his legs as it were, and he was really miserable for about a couple of weeks. He was really fed up and he says, ‘No, no, I cannae go on like that. I’m going back tae that man.’

So back he went to Kathy ‘s father and he says, ‘Look, I just can’t live withoot Kathy ,’ he says. ‘I can’t live withoot her,’ he says, ‘I just can’t.’ And he says, ‘Well, it looks as if she feels the same,’ he says, ‘Because she’s lyin there greetin’ every nicht.’

He says, ‘Look, there must be some way that I can marry Kathy , there must be.’

‘Well,’ the father says, ‘There’s only one way. If you agree to become a good devout Catholic,’ he says, ‘A’ll let you get married.’

He says, ‘Ach, if that’s aa there is tae it, A’ll soon dae that.’

So Kathy and John they went tae the priest and they went through whatever rigmarole you go through to become a Catholic. And they cam’ back and they got married and they even found a wee place tae stay. And all was going fine with them, they were quite happy for about a month or so.

But after about a month Sean said one day to Kathy , ‘Look, Kathy ,’ he says, ‘I work aa week and I work hard,’ he says, ‘and aa the weekdays we maybe have porridge or kale or something like that. And I give you ma pay on a Thursday night, and every Friday,’ he says, ‘you set doon fish in front o’ me – the only day we can hae a decent meal you come and hand me fish. I dinnae like fish, I never liked fish.’

And she says, ‘But..’

And he says, ‘Look when I come home tonight I want a steak – a nice juicy steak.’ ‘I’m sorry, Sean,’ she says, ‘I cannae gie ye a steak.’ She says, ‘You’re a Catholic and if you want anything at aa that we cry ‘kitchen,’ it’ll have tae be fish.’

And he says, ‘Well I dinnae want your fish.’ And they fell oot aboot that and away he stamped oot tae his work and when he cam’ hame, sure enough his fish was on the table.

He says, ‘I thought I telt you that I dinnae want fish.’ And she says, ‘I’m sorry tae tell you that ye’ll hae tae tak fish whether ye like it or no.’

And this started up again with their first big argument aboot this fish and this steak. So, they settled doon after a while and Kathy says, ‘Sean,’ she said, ‘You should go back tae the priest because Catholics dinnae eat any kind o’ meat except fish on a Friday.’

And he says, ‘Well I cannae help it, the Catholic…’

She says, ‘Look, you promised tae be a good Catholic so I think ye should go back to the priest and he’ll help ye.’

So back he went to… this Catholic priest. And the priest said, ‘Well there’s really nae mair that I can tell ye, Sean,’ he said, ‘I went through the whole thing wi’ you., there’s only one thing I can say to you: you should keep saying to yirsel’ “I’m a Catholic, I’m not a Protestant, I’m a Catholic, I’m not a Protestant.”‘

And he says, ‘Aaricht, A’ll dae that then.’ So away he went.

Now a few weeks after that the priest happened to be cycling past their door and he says, ‘Ach, I’ll go in and see how Kathy and Sean’s getting on.’ So he jumped aff o’ his bike and in he went and Kathy was standing there in the living room. And he says, ‘Where’s Sean?’

She says, ‘Sean’s ben there, in the scullery,’ she says, ‘just ben there.’

So the priest opened the door of the scullery and and the savour o’ this roast almost knocked him doon. And Sean was there wi’ a pan in his hand and he was spooning the gravy ower this fine juicy steak. And he was spooning the gravy ower it and he was saying to himself, ‘I’m a CATHOLIC, I’m NOT a PROTESTANT. I’m a CATHOLIC I’m not a PROTESTANT. And YOU are a FISH! You’re NOT a STEAK!”

——————

Betsy’s toast.

Well here’s tae yeez aa, as good as yeez are,

And here’s tae masel, as bad as I am,

But as bad as I am, and as good as yeez are,

I’m as good as the best o’ ye, as bad as I am.

———————-

More to follow in the next week or so.

Thank you.

I listen to her recordings on Tobar an Dualchais all the time. I wish I’d known her & feel like I do.

I try to learn some of her songs.

It scares me to read she died at the age I am now, 69.

Dear Joan, thanks for your comments. Betsy was a lovely person to know. Which is your favourite song? Fragments of her songs keep running through my head wherever I am. It was a shame abaut her death but she did smoke a lot and when I knew her spent most of her time sitting around chatting with friends and visitors. As you could guess she enjoyed a good crack; but I think performing and drinking at a folk club meeting on her last evening proved a little too much for her. I was overseas at time so did not hear of her death for a while. One does worry about one’s own mortality from time to time but as I’ll be 90 in a fornight’s time I’ve now given up worrying except for how to dispose of all my clobber – notes, records, CDs etc. etc. so that no-one else has to do it!

Peter! lovely to read this blog about the incomparable Betsy Whyte (and find your other fascinating pieces). I tried emailing u at a possibly out of date address, re contact for David Pullar BUT have found him anyway and had a good chat. I’ll gather some memories & mementoes of Bessie to send him, he is clearly the family person to whom these should go. I was in Auchtermuchty 32 years ago the other day, staying c/o Linda & Duncan with Bessie & Bryce in their caravan nearby and have a clear, if poignant, picture still of her last night. She insisted, at some unearthly hour, that I sing The Rue and the Thyme which she had written out for me – her mother used to sing it a lot – as she wished it to carry on. It was a privilege to get to know her and Bryce, and sister Katie, and that was thanks to common friends in Edinburgh and my involvement in the School. Am still doing Iona-related projects by the way, linked to my research then. And my partner, Bob Pegg, is still composing music & song despite the limits of lockdown. We’re lucky to live up a hill in Strathpeffer in these times. All best wishes, Mairi