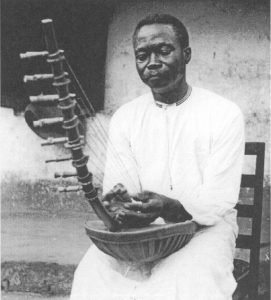

Evaristo Muyinda was one of Buganda’s best known traditional musicians throughout the second half of the 20th century – versatile and with a a deep knowledge of the royal repertory. These are notes cobbled together from my files in response to a query on Facebook. Inevitably they mostly result from Muyinda’s association with bazungu (Europeans). The last item on this page is an English translation of a moving story told by Muyinda himself about one of the most famous royal songs, Omusango gw’abalere.

Klaus Wachsmann invited Evaristo Muyinda (a former member of Kabaka’s akadinda – xylophone – team ) to work with him at the new Uganda Museum in 1948, because as the new curator Wachsmann wanted the museum to be a living museum resounding with the sounds of live music demonstrations and music instrument teaching. It was because of Muyinda that Wachsmann made numerous recordings of the akadinda team in the Lubiri (the Kabaka’s palace) but strangely none of Muyinda himself though he worked closely with Wachsmann for years. The akadinda pieces can be heard on line at the BL Sounds website. Try a search at BL Sounds for ‘Muyinda’ and they should all be found.

Two important published CDs:-

“EVARISTO MUYINDA: Traditional Music of the Baganda as formerly played at the court of the Kabaka.” CD 54 Pan Ethnic series Pan 2003CD Pan Records PO Box 155 300 AD Leiden Netherlands. Recorded on Jan 17 1991 at Kanyanya by Joop Veuger

“THE KING’S MUSICIANS: ROYALIST MUSIC OF BUGANDA”. Topic Records TSCD 925. London. Compiled by Peter Cooke. 2003. This CD includes a track where Evaristo Muyinda beautifully tells the story of Ssematimba ne Kikwabanga. This track can also be heard online at BL Sounds, as can his equally interesting telling of the story of the song Omusango gw’abalere. You can read an English translation of this second song if you scroll to the bottom of this page.

Several recordings were made by Hugh Tracey in 1952 during one of his fieldwork visits from South Africa and were later published. Tracey recordings include:- TR 139.B2 Munya gweriira munale, also Ssewasswa kazaabalongo. For a list of Tracey’s Uganda recordings, a number of which involve Muyinda, consult http://samap.ukzn.ac.za/

A few recordings of Muyinda are now archived at the Calloway Centre, University of Western Australia as part of the John Blacking Collection. Until his death John was Professor of Social Anthropology at Queens University Belfast. He visited Makerere in 1965 to give seminars on music and social anthropology and visited several parts of Uganda with students to demonstrate fieldwork methods.

One of the recordings he made was at a public concert in the Uganda Museum – the song called Akawologoma – a royal flute song played on three endere flutes by Evaristo Muyinda, Albert Ssempeke and Ludovico Serwanga. It was recorded in the rather echo-y museum hall and is a somewhat distant recording.

Janice Hobday (formerly music teacher at Gayaza Girls School during the period 1960s-70s) From an interview with Peter Cooke 2014)

“We had Mr Muyinda – the girls learned drumming and xylophone. He used to come every Saturday. The girls went to the Uganda Museum first (where he worked) but then he came to them. We always had an audience. During prep time they were allowed to go off prep – that was their music prep.” She thinks he was a very good teacher

Gerhard Kubik “In Uganda I was lucky. Almost upon arrival in Kampala, I found a teacher in Kiganda music. In my innocence I did not realize that my search for a Muganda teacher would raise eyebrows in colonial circles. At least those eyebrows did not hurt. I found a teacher in Evaristo Muyinda, who was a former Kabaka’s (King’s) musician. He had worked before with Klaus Wachsmann and Joseph Kyagambiddwa, and was in charge of the performance of court music at the Uganda Museum. Muyinda became a father-like person to me. He was a benevolent and friendly teacher. He began by holding my hands to teach me the correct movement when striking the slats of an amadinda xylophone and he showed me how to keep my wrists flexible when playing in parallel octaves through the equidistant pentatonic system….” (‘Interconnectedness in Ethnomusicological Research’, in Ethnomusicology, 44/1 Winter 2000 p. 1.

Lois Anderson in her doctoral thesis on the Kiganda Miko system. (c 1968) wrote:-

“I went daily to the Uganda Museum and Mr. Muyinda taught me various songs. He followed a definite pattern in his teaching method. When I had learned one of the individual parts of a song to his satisfaction, he would combine the second part of the melody with the part that I was playing to make sure that I was able to sustain my part. At this point I would notate the part that I had just learned in cipher notation. I followed the same procedure in learning the second part to the melody. In order to learn the precise method of interlocking the two parts, I played Part A, the first part, over and over while Mr. Muyinda inserted a few notes of Part B, the second part, at the exact place where the two parts should be combined. He repeated this process until I learned the precise place in Part A where Part B was inserted and also the particular portion of Part B which was used for this process. We then changed roles and it was my function to put into practice the process of combining Part B with Part A correctly. I then made notes of the manner of combining Parts A and B.” (Anderson 1968: 3-4)

Robert Walser from his MA thesis lodged at the School of Oriental and African Studies, London.

“One of Wachsmann’s key contributions resulted from his hiring Evaristo Muyinda (born 1914) to give musical demonstrations at the Uganda Museum where he worked from 1948 or 1949 to 1982. Muyinda was a member of the kabaka’s akadinda team and learned to play other instruments as well eventually becoming a key link between European scholars and Ugandan music, particularly the amadinda xylophone. The first European to write of learning under Muyinda was Gerhard Kubik.”

From Kasule and Cooke’s article in African Music Journal, Vol. vii/4, (1999), 66-72 “The musical Scene in Uganda”

“This diversification of instrumentation was partly inspired by the former National Ensemble which, under the musical leadership of the distinguished muganda musician Evaristo Muyinda, had been resident at the National Theatre in Kampala up to the early 1970s and had provided much music for the national dance troupe Heartbeat of Africa. This was Muyinda’s so-called ‘Kiganda orchestra’. Its personnel were mixed ethnically (though with baganda and basoga musicians forming the majority) and the whole was modelled on the lines of a western ensemble with groups of instruments of contrasted tone colours (tube fiddles, lyres, flutes, pan-pipes and zithers), mingling and contrasting their sounds with those of xylophone, drums and rattles.”

Peter Cooke and his son Andrew (born in Kamapala in 1965) worked frequently with Muyinda. Cooke senr. came to teach at Makerere College School in 1964 and found Muyinda teaching kiganda music and dance there on Wednesday afternoons. Muyinda’s dance group together with the school choir won the Caltex Festival Cup in 1965.

Both Peter and Andrew met with Muyinda again much later – in 1987 and 1988 – when Muyinda came with his group to perform in the UK and Europe. While on tour in London in 1987 Muyinda fell seriously ill as a result of an enlarged prostate. Both Cookes (in Edinburgh) telephoned the doctors at the London hospital to persuade them to operate – they had been unwilling unless Muyinda could produce in advance the money to pay for such an operation and apparently the British Council which had facilitated the tour would not or could not help. The hospital surgeon was persuaded to deem Muyinda’s problem ‘life threatening’ in which case the operation could proceed without prior payment. The operation went ahead and Muyinda returned to Uganda with a bill for several thousand pounds (which all knew – hospital staff included – that he would never be in a position to pay). A very satisfactory outcome! He returned to good health very quickly.

Both Cookes visited Evaristo Muyinda at his home when they returned to Uganda later the same year.

——————–

The following recordings of Muyinda are excerpted from Peter Cooke’s index to his tape archive. All recordings are available at Makerere University Klaus Wachsmann Archive and at British Library’s on-line archive (BL Sounds).

numb PCUG87.13.4

plac Mr Muyinda’s home at Mpererwe (Gayaza road)

date 17.9.87

inf Mr and Mrs Muyinda and friends with Andrew Cooke

titl –

type General cries of welcome and chat in Luganda

summ Recorded during first visit to Mr Muyinda after his trip to UK. Sounds of ndingidi being tuned up in background

numb PCUG87.14.1

plac Mr Muyinda’s home at Mpererwe (Gayaza road)

date 17.9.87

inf Mr and Mrs Muyinda and friends

titl Twabalamusa ffenna bwetwa alaba ‘agenyi

type Trad. Kiganda song.

summ Begun with Mr Muyinda announcing the tune on an endere

(flute). Accompanied with handclapping. Interrupted – was only a practice.

numb PCUG87.14.2

plac Mr Muyinda’s home at Mpererwe (Gayaza road)

date 17.9.87

inf Mr and Mrs Muyinda and friends

titl Twabalamusa, ffenna…

type Trad. Kiganda song.

summ Repeat of first item but with drums and rattles as well as flute. Played in honour of Andrew Cooke.

numb PCUG87.14.3

plac Mr Muyinda’s home at Mpererwe

date 17.9.87

inf Mr and Mrs Muyinda and friends

titl Omusango gw’abalere (the case of the flutists)

type Trad. Kiganda historical song

summ With flute, ndingidi, rattle and drums. Mr Muyinda singing many of the solo lines and playing ndingidi. Has a false start. Translation. by Miriam Zziwa.

numb PCUG87.14.4

plac Mr Muyinda’s home.

date 17.9.87

inf Mr Muyinda

titl Akawologoma (little Lion)

type Trad. Kiganda historical royal song

summ Mr. Muyinda plays baakisimba and ngalabi simultaneously to accompany his singing. Moves without a break into the next item

numb PCUG87.14.

plac Mr Muyinda’s home.

date 17.9.87

inf Mr Muyinda

titl –

type Trad. Kiganda drum rhythms with words.

summ Mr Muyinda drums while chanting the appropriate words for a variety of traditional rhythms. Duration 1’40”

numb PCUG87.14.6

plac Mr Muyinda’s home.

date 17.9.87

inf Mr and Mrs Muyinda and friends

titl -?

type Trad. Kiganda song

summ Opening phrase missed. With a full drum and rattle accompaniment. Two different soloists, Mr Muyinda and another. Tape runs out before end.

numb PCUG87.27.2

plac Evaristo Muyinda’s home.

date 28.9.87

inf Evaristo Muyinda

titl Ssematimba ne Kikwabanga

type Historical song sung to endongo (lyre) accompaniment

summ 4’50”

numb PCUG87.27.3

plac Evaristo Muyinda’s home.

date 28.9.8

inf Evaristo Muyinda

titl Ssematimba ne Kikwabanga

type Historical tradition – story of the two princes.

summ told by E. Muyinda., with explanations of song text. Followed by questions from fieldworker about which groups perform the song. The song is sung at mourning rites and at okwabye olumbe. Hudson Kiyaga adds a little information on this at end of Muyinda’s contribution.

numb PCUG87.27.4

plac Evaristo Muyinda’s home.

date 28.9.87

inf Evaristo Muyinda

titl Omusango gw’abalere (the case of the flutists)

type Historical tradition linked to the song – Long v. interesting story.

summ Speed switched to 3 3/4i.p.s for this story.

numb PCUG87.27.5

plac Evaristo Muyinda’s home.

date 28.9.87

inf Evaristo Muyinda

titl Asigala atalama (He who does not depart, cannot make a will)

type Historical tradition associated with the song

summ Recorded at 3 3/4 ips.

numb PCUG87.28.1

plac Evaristo Muyinda’s home

date 28.9.87

inf Evaristo Muyinda’s group

titl ?

type Kiganda baakisimba dance song

summ Drums rather loud at start. Songs begins with tube fiddle. 2 tube fiddles, singer and amadinda xylophone. Muyinda changes to ndere later. Singing stops well before end of item. A good ending. Switched back to 7 1/2 ips

numb PCUG87.28.2

plac Evaristo Muyinda’s home

date 28.9.87

inf Evaristo Muyinda’s group

titl Nnamayanja webale (Thankyou, Nnamayanja)

type Kiganda baakisimba dance song

summ instruments include 2 tube fiddles and xylophone and drums. A good ending.

numb PCUG87.28.3

plac Evaristo Muyinda’s home

date 28.9.87

inf Evaristo Muyinda’s group

titl ?

type Kiganda embaga dance song

summ Hot drumming! Good singing and good ending. Fairly short song.

numb PCUG87.28.4

plac Evaristo Muyinda’s home

date 28.9.87

inf Evaristo Muyinda’s group

titl Olwaleero (Because of today)

type Kiganda baakisimba dance song

summ 2 tube fiddles and endongo (lyre). Good ngalabi playing. Balance fairly good – rattles and ngalabi rather loud at one point. Neat ending.

nu PCUG92.9.2 (pgm 02)

d 7.2.92

pl Evaristo Muyinda’s home.

in Evaristo Muyinda

t Veneneka (Veronica)

ty Amadinda song on small amadinda.

su Preceded by chat with Muyinda asking if he knows certain songs. Mr Muyinda says he doesn’t know entenga music. Plays Veneneka on his small amadinda with Andrew Cooke. Playing begins c. 6′ Okunaga part is played over.

nu PCUG92.9.3 (pgm 03)

d 7.2.92

pl Evaristo Muyinda’s home.

in Evaristo Muyinda with Andy Cooke

t Mubandusa (Ebyasi…)

ty Amadinda song on small amadinda.

su Muyinda sings versions of the song

nu PCUG92.9.4 (pgm 04)

d 7.2.92

pl Evaristo Muyinda’s home .

in Evaristo Muyinda with Andy cooke

t Nandikuwadde (Kalagala e Bbembe)

ty Amadinda song on small amadinda

su Mr Muyinda plays with Andrew on small madinda and then sings texts beginning c. 17′ 34″

Nu PCUG92.9.5 (pgm 05)

d 7.2.92

pl Evaristo Muyinda’s home.

in Evaristo Muyinda with Andy Cooke

t Kawumpuli (Plague)

ty Amadinda song on small amadinda.

su Muyinda sings words beginning c 20′ 20″. Muyinda is asked for the story about the song. Gives a brief explanation. This plague works very quickly, by one or two oclock one is dead. Possibly dates back to Kabaka Kyabaggu. Then he takes his harp to tune it and is recorded doing so.

Nu PCUG92.9.6 (pgm 05)

d 7.2.92

pl Evaristo Muyinda’s home.

in Evaristo Muyinda

t Kansimbe omuggo awaali kibuka

ty Ganda trad. song sung to ennanga (harp accompaniment).

su Muyinda first tunes his harp . Brief performance begins c 30’nu PCUG92.9.7 (pgm 05)

fw Peter Cooke

d 7.2.92

pl Evaristo Muyinda’s home.

in Evaristo Muyinda

t Gganga

ty Royal song to ennanga harp accompaniment

su Brief performance. begins c. 31′ 30″: some chat and gentle playing follows this, with a fragment of Olutalo Olwe Nsinsi. (Andy Cooke probably playing harp).

The Story of “Omusango Gw’Abalere gwegaludde, Bantwale e Bbira gye banzaala”. Everisto Muyinda, tape PCUG87.27.4

translated by Miriam Zziwa and Dr Sam Kasule.

That song, “The case of the flutists has been exposed, Let them take me to Bbira where I was born’”. It started like this:-

Long ago – [during the time of ] the Kings of long ago, there were flutists who were in the palace of the king. One of the ways of the palace was that if you were a servant in the palace – inside the palace compound, – you all called the king your ‘husband’. Now everywhere it was the custom that you must follow proper traditions inside the palace. You must greet a royal man and show him the respect that his royal rank deserves. You should also show respect to to the royal women. You don’t stand anyhow when greeting them – and [when greeting] the wives of the men of the palace you don’t stand anyhow. To stand anyhow means standing and greeting them in a casual manner like you do with any ordinary person with “How are you? How are things at your place”. Well then – you must humble yourself for him or her, or if you have knelt down – for it is the tradition everywhere that you kneel.

But in the palace there were flutists, the flute ensemble. They were the ones that laid down grass in the houses of the wives – for those wives were not allowed to go cutting tteete grass in the jungle for spreading down in their houses. Those flutists were the ones to come and lay the grass in the wives’ houses. But one day those flutists refused to greet the Kabaka’s wives while kneeling, saying instead “All of us [you too] have the same husband [i.e. we are equal in rank]. We call him ‘our husband’ and you call him ‘your husband’ and so why should we kneel for you? We will not kneel for you.”

Now the matter was taken to the king, their ‘husband’ and they told him that the flutists this day have rebelled – ‘they have refused to greet us in a proper way. After that we quarreled and they look down on us.” Now, when he heard – you understand – such words coming from the wives as they heard it, the king was annoyed, he ordered those flutists to be detained and brought before him, bringing them by force if need be. Now the beloved women – when they reached the flutists – the flutists had already got to know of the plan and they ran away from the palace, breaking out and running off to their homes.

Now they had their village – Kalungu – the place where the flutists used to gather and where the leader of the flutists who instructed them in fluting had his home.

Now, they went there, but around that time – as you know, illness comes without warning – the king died while the flutists were still away. After his death this child who succeeded him [Daudi chwa], who took his place as king, had learned to enjoy listening to flutes very much and he asked of his father’s flutists who used to play the flutes, “Where did they go?” And they explained to him that – eh – they went away and are at a village called Kalungu. And he said “Aah”. Then he sent a messenger whom he told to go and bring them. OK, when they reached Kalungu they were informed that the Kabaka needed them.

Well, because they had left the palace for doing wrong they thought, “Oh! That crime that we committed has been raised again.” Being raised again means to resume. “So it has resumed – oh dear! This is a sad event.” And they began assembling and played their flutes, sounding a song for mourning, just mourning. And saying “Yi!” – the flutists – “this crime has been taken up again. Now let them take us and let us plead our case”. Because during that time the Kabaka used to listen to cases at Mugema’s place and Mugema used to live at Bbira village – him, the grandfather of Buganda. Now they started to sound that song on their flutes “Omusango gw’abalere gwe galudde, Bantwale e Bbira gye batuzaala” [The case of the flutists has been taken up again, let them take us to Bbira where we originated], “For what will we say? There’s nowhere we can go”.

They came [to Bbira], and when they reached the place of judgement they processed along sounding the song on their flutes and beating their drums – but it was that lament, as the words go- “The case of the flutists has been taken up again”. There they are – going along and playing and singing that song, and it amused the Kabaka very much.

Now when they finished there he commanded a page to ask of them saying “What’s the name of that song?”. Now when the page asked them, instead of replying that we call this song “Omusango gw’abalere..” they changed the name and said that they call the song “Ndigenda n’abalere gwegaludde ab’e Kalungu, bantwaale e Bbira gyebanzaala” – [I will go with the flutists of Kalungu, let them take us to Bbira where I was born]. Oh! Oh!. He was delighted and he gave them drinks and gave them eats and he provided many little delicacies and treated them extremely well. The flutists found their confidence restored when he made this following request, “My dear friends, I also want to learn the flute.” That flute which they cut for him and prepared for him, they called it “Lumonyere, the flute of Ssuna.” Because [Kabaka] Ssuna also was very fond of the flute and he was always asking them, “Play my song,” over and over again – and that was how he learned the skill. Now because he used to say this repeatedly like ‘olumonyere’ which means ‘something that never stops, on and on, on and on, “Do that again. Do that again” – that is what is called ‘olumonyere’. And even his flute, he called it “Olumonyere, the flute of Ssuna”. And he played the flute so well with the result that the flute became the favourite and their master was taught well.

That is where that song originated. But because when you are singing you cannot sing isolated words “I will go with the flutists of Kalungu, let them take me to Bbira – I will go with the flutists.” Well, they go joining the words all together. They would go singing and with the instruments all sounding, beating nicely on the baakisimba (dance drum), the engalabi (long drum), ensaasi (rattles), and the flutes – which altogether are six in number in their group.

Now round about the time that they were singing there was a child who was disrespectful to his mother. There was this child and in his father’s house there were two mothers. On the one side there is this small child – on the other, this old parent- his stepmother, and she sent the child saying, “Fetch me some fire.” The child refused her bidding and yet this woman’s children had died, and in spite of this fact this child hurt the stepmother’s feeling. And he told her “Sekatumira abaana, atumatuma abaana ababo bewazala – “You, bossyboots, where are the children you gave birth to?” “Oh, Maama!” sighed the mother, “Ah! My child, you are such a sweet young creature! Don’t be sarcastic like that. I bore mine for the soil”. Then the child replied, saying. “If you bore them for the soil, call them to come and bring you fire”. “Right, said another one there, “When I looked at my mother, I saw she was helpless, to look at [Father***?** ] I saw he is all alone.” Then this woman wept and while she was weeping another child asked her “Mama, you, – Daddy’s friend, seated by the door post crying. What can tears bring back? Calm down, I’ll bring the fire for you.”

This other child helped the woman and brought her fire. Right then, the story goes on – “You who like to order children about, show us your own children.”

It continues like this:-

“You who order children about, show us your own children”. If you talk like that tears will be the outcome. Looking at my mother I see she is alone, I can see she is helpless. The bushy plot behind the house became the track of the civet cat. Because then her plantation had become overgrown, because she was helpless and unable to cultivate it. Because what used to be a house has become couch grass smothering the house.

Now, they continue singing – “What used to be Father’s plantation , Maama’s plantation that’s where hunters look for game.” Those gardens that belonged to Father, builders collect reeds there because the gardens are now wild, they collect reeds there. Now, more words are added on to that song . Because of grief, “I don’t know if I will go into space [as a spirit] “, – You know when you die they bury you in open space, the sun shines on you – ” Or if I will be put into the tall grass – which will prick my body”. Now they continue singing that song until they add on more words and it grows large.

Now imagine for example that when you die your father is dead, you may say , “Ayi! Father’s gardens have grown wild. Now builders collect reeds from there. What used to be coffee trees are now dried and gone wild and have been burnt as bush and you collect firewood from there since they are dry. Now, my friend, this lonely journey disturbs my mind. Oh my friends”. When you die they bury you on the edge. Because they don’t bury you in your compound as if you never used to sweep it. That used to make people cry a lot. “If you die they put you in the garden as if you never built a house – they remove you from your house and put you outside as if you never built a house.”

Now that song continues collecting such ideas about human grief and they sing that song “Omusango Gw’Abalere gwegaludde Bantwale e Bbira gye banzaala”. That’s how it goes. Those words as sung in the song while they are playing instruments, or blow flutes or sing, or beat the bakisimba or play the xylophone. If one knows how to sing well with the xylophone or with the harp he sings such words because he can see that they are all concerned with human grief: this is all connected with the original lament of the Abalere. Now it touches everybody who has any sorrow in their hearts. My friends, those are the texts to sing for the song “Omusango gw’abalere gwegaludde“.

What a story! Thanks alot @Cook.